Lessons from wolves

For decades, scientists have been following a population of wolves on Isle Royale that has served as a model system for the study of the evolution and genetics of small, isolated populations. Isle Royale is a remote island in Lake Superior, USA, and wolves first arrived via an ice bridge from Canada in the 1940's. They found a healthy population of moose and no other predators, and their numbers grew. Over the years, the populations of the wolves and moose cycled in the dynamics of predator and prey. Good years for the moose population would be followed by an explosion in the number of wolves, which would drive the moose population back down, and the cycle would begin again. Scientists were able to observe the effects of the introduction of canine parvovirus, which nearly wiped out the wolf population in the 1980s. When the wolf population failed to recover, despite an abundance of moose to support them, scientists became concerned that the population was suffering from the negative effects of inbreeding. The wolf population was descended from only one male and two females.

A hard winter in 1996 took a heavy toll on the moose population, which collapsed to only 500 animals. This reduced the available food for the wolf population that was still trying to recover from low numbers.

A hard winter in 1996 took a heavy toll on the moose population, which collapsed to only 500 animals. This reduced the available food for the wolf population that was still trying to recover from low numbers.

http://www.isleroyalewolf.org/overview/overview/at_a_glance.html

http://www.isleroyalewolf.org/overview/overview/at_a_glance.html

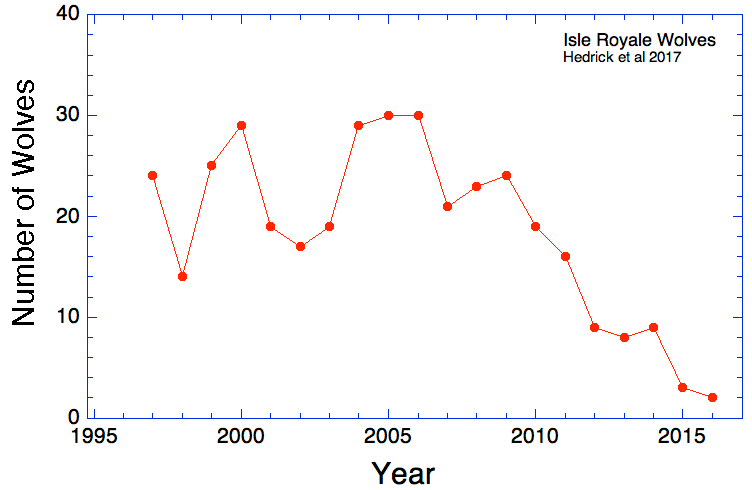

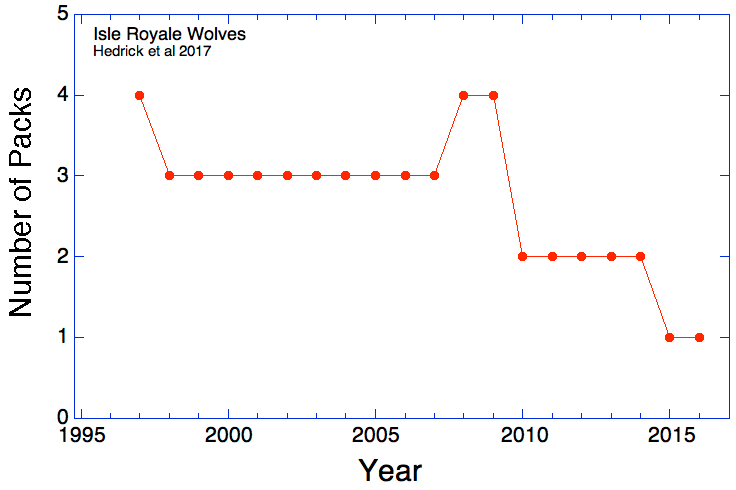

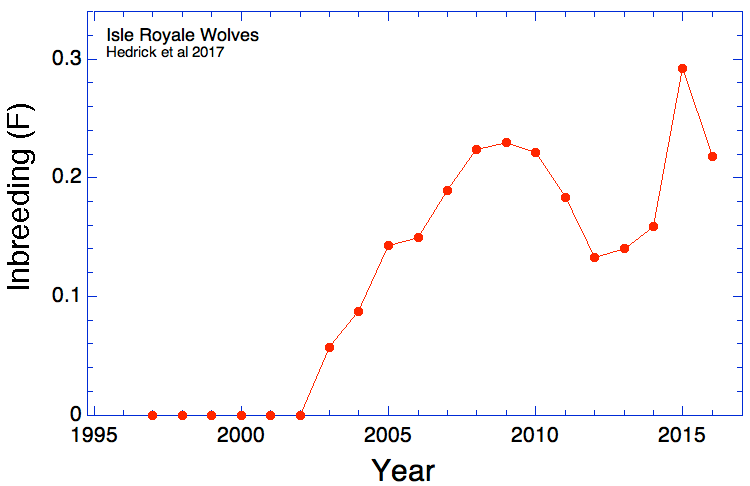

Then in 1997, a wolf called "Old Grey Guy" (designated "M93") crossed the ice bridge that occasionally forms between the island and the mainland and joined the population on Isle Royale. With the injection of fresh genetic diversity from an unrelated animal into the population, the wolves began to thrive and increased from three packs to four. But the superior health and fertility of M93's descendants allowed them to proliferate at the expense of the older lineages until nearly 60% of the genetic variation in the population came from M93. As the level of relatedness of the animals in the population increased, so too did inbreeding. Pack after pack failed until by 2011 there was only a single pack of nine wolves remaining on Isle Royale.

Today, only two closely-related wolves are left. They are half-sibs and also father-daughter. If they produced a pup, the expected level of inbreeding would be 44%. It is possible that, just by chance, they are less related than would be expected from their pedigree relationships, and if they produced a pup it might, just by chance, be less inbred than predicted. But in the absence of new blood added to the population, inbreeding can only increase. The last pup seen with the pair in 2016 was deformed and small in size, and it disappeared in 2016. This is probably the end of the road for the Isle Royal wolves.

The graphs below are from a paper just published that documents the genetic and population deterioration of the Isle Royale wolves from 1995 to the present (Hedrick et al 2017). They tell a simple story. A small, isolated population of animals initially thrived, but a series of unfortunate environmental events and unavoidable inbreeding have resulted in collapse and probably extinction.

Nothing about the Isle Royale wolf story is a surprise. Inbreeding and loss of genetic diversity reduce the ability of a population to tolerate changes in environmental conditions, disease, fluctuating food supply, and the many other random events that can affect survival in the wild. Eventually, animals in closed, isolated populations go extinct.

Our purebred dogs don't have to survive extreme weather and occasional food shortages. We assist reproduction, nurse the weak pup, avoid allergies with special diets, and otherwise keep the dogs as healthy as possible with the best veterinary care. But it's sobering to compare the levels of inbreeding that did in this population of wolves to those typical of purebred dogs. Before the arrival of M93, the average inbreeding in the wolves was a bit more than 20%. After a few generations, inbreeding began to increase again and was most recently greater than 30%. In the vast majority of purebred dog breeds, the average level of inbreeding exceeds 25% and in too many breeds exceeds 40%. For breeds with closed stud books, inbreeding can only continue to increase. The Isle Royale wolves provide a real-life experiment confirming what we know about the consequences of small population size and genetic isolation.

We are inadvertently repeating this experiment, now with a captive population of purebred dogs. How high can the level of inbreeding go before a breed simply goes extinct? Do we really want to find out?

We are inadvertently repeating this experiment, now with a captive population of purebred dogs. How high can the level of inbreeding go before a breed simply goes extinct? Do we really want to find out?

Carol Beuchat PhD

Source: http://www.instituteofcaninebiology.org/blog/lessons-from-wolves

REFERENCES

Hedrick PW, M Kardos, R Peterson, & JA Vucetich. 2017. Genomic variation of inbreeding and ancestry in the remaining two Isle Royale wolves. J Heredity (in press).

Hedrick PW, M Kardos, R Peterson, & JA Vucetich. 2017. Genomic variation of inbreeding and ancestry in the remaining two Isle Royale wolves. J Heredity (in press).

- Log in to post comments